You spot the shiny car that’s been haunting your dreams, and the salesperson says: “The model starts at X, but if you liked wheels, windows and steering wheel, let’s look at the options sheet.”

Companies make their real money from their core portfolio — their products that keep the lights on. Core portfolio includes the product versions that cover the big chunks of customer segments.

But to boost performance further, they create different combinations of values that meet different needs. With add-ons (extras, features) you can tackle more specific needs of often smaller customer groups, which adds more business potential.

Let’s pop the hood and explore what challenges companies face when they balance their core products with add-ons, why it’s trickier than bolting on a spoiler.

When you walk into a dealership, you don’t just see one shiny model parked on a pedestal. You see a lineup of vehicles, each one tailored to a different kind of driver:

That lineup is the core portfolio — the collection of models that meets the fundamental transportation needs of different customer segments. This lineup is what makes or breaks the company’s financials. If you don’t have the right set of models to meet these fundamental needs, no amount of chrome trim or heated cupholders will save you.

But once the basics are covered, the danger creeps in: saturation. Every automaker eventually offers a version of each model type. Customers still need these cars, but the thrill of choosing between them fades.

That’s where product versions and add-ons come into play. These are not new “vehicle types” but features that enhance the lineup: upgraded trims, smarter infotainment systems, safety packages, and quirky accessories - they give each car personality. In other words: the core portfolio covers the “must-have” transportation needs, while product versions and add-ons tap into the “nice-to-have” desires that make customers feel they’ve chosen their car, not just a car.

Cars (and products) don’t stand still. They evolve through four stages that map perfectly onto the product evolution model.

Base product: “It gets you there”

Think of the no-frills base model: four wheels, an engine, maybe an FM radio if you’re lucky. In product terms, this is the stripped-down version that solves the most basic need.

Expected product: “It gets you there the way it should”

Automatic windows, Bluetooth, air conditioning, or airbags. At some point, these features were not included, but after a while they became expected. Customers don’t thank you for them anymore; they walk away if they’re missing.

Extended product: “It gets you there the way it should and makes you smile”

Now we’re talking heated seats, surround sound, and advanced driver assistance. These features create delight by adding value to certain customer groups and to certain and usually more specific needs not everyone has. They’re add-ons at first, but they might become the reason customers pick your car over the competition.

Potential product: “It could drive you to Mars”

This is the dream factory — autonomous driving, flying cars, AI copilots. These represent the future potential of the lineup. They’re not selling in volume yet, but they inspire, attract attention. Companies invest in these because they define the future, even if the present still struggles with parallel parking.

The key insight: add-ons are the gears that shift your product up these stages.

If add-ons are so powerful, why don’t companies pile them on like a dealer slapping chrome onto every surface? Because add-ons are trickier than they look.

Customers aren’t used to them

New add-ons can feel awkward, either because customers don’t see the value yet, or because they don’t expect you (as a company) to provide them. A brand that sells simple trucks may struggle to convince drivers to buy fancy infotainment subscriptions. Proper timing plays a critical role.

The core portfolio hogs the spotlight

The car launch is the red-carpet moment. The new trim options? They get buried on page 17 of the brochure. Companies pour attention into core products because they’re the revenue engines, that’s where the big money is earned. Similarly, the front line representatives are more familiar with the core offerings, they are incentivised to make that sale primarily. The focus and the capacity is always there.

Not all add-ons are created equal. You can serve them up in different ways.

You can manage the profitability easily in case of standalone, and as you include more items, this game gets trickier. In a package, you can control the combination of margins and set the proper price to ensure that, but in a pool of different profitability levels, it gets really challenging as part of the control gets to the customer.

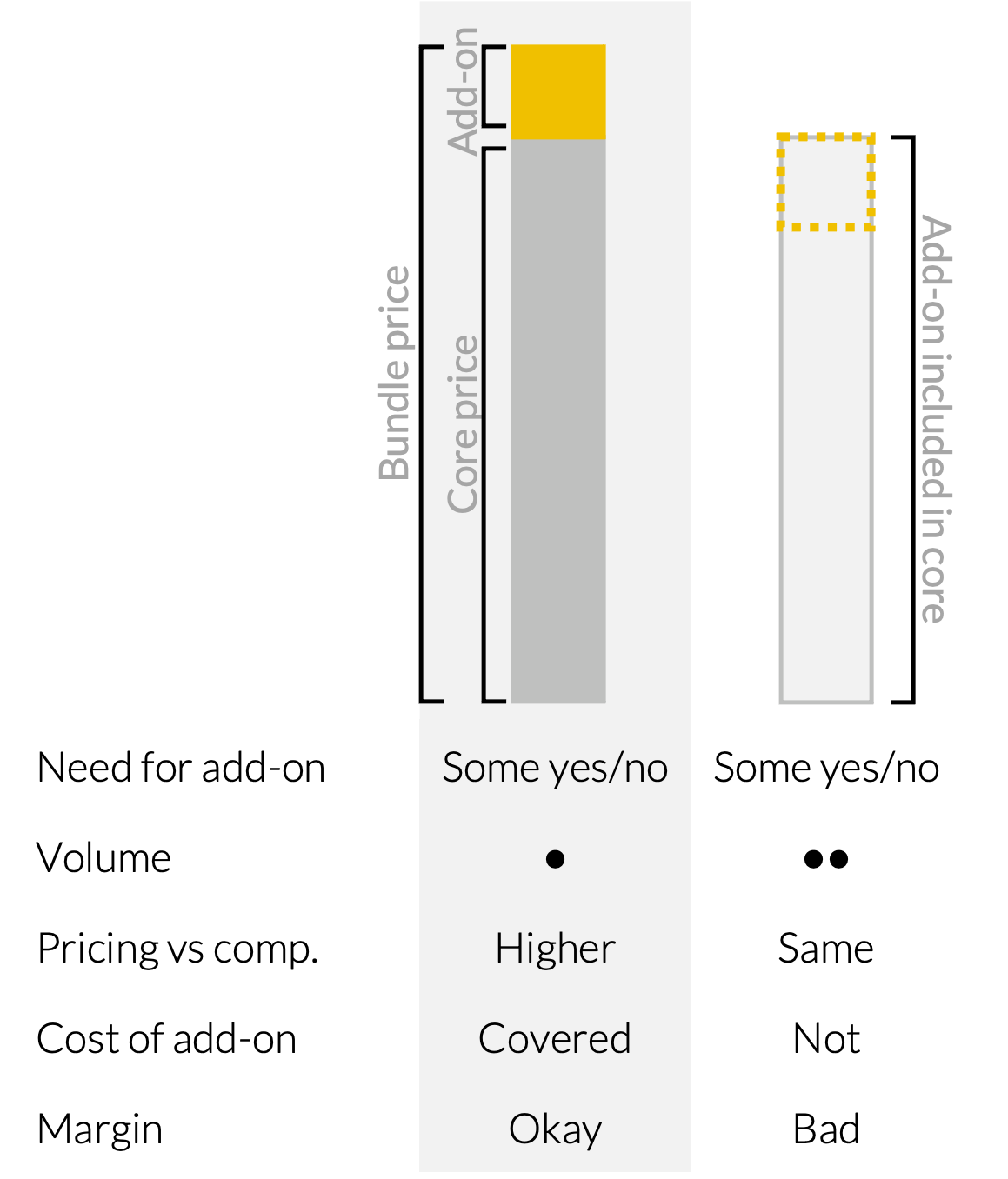

When it comes to the in-bundle version, it can easily be a zero-sum game in the beginning.

When the new feature is not widely spread yet, you face a hard challenge. You either overprice your product when the feature is not expected yet and customers don’t attach value to it, so they simply look at the base product and compare it with other vendor’s base product, or you ruin your margin level by offering more value at the same standard price as others on the market.

In 1:1 type of standalone add-on, you sell the product to those who clearly demand it.

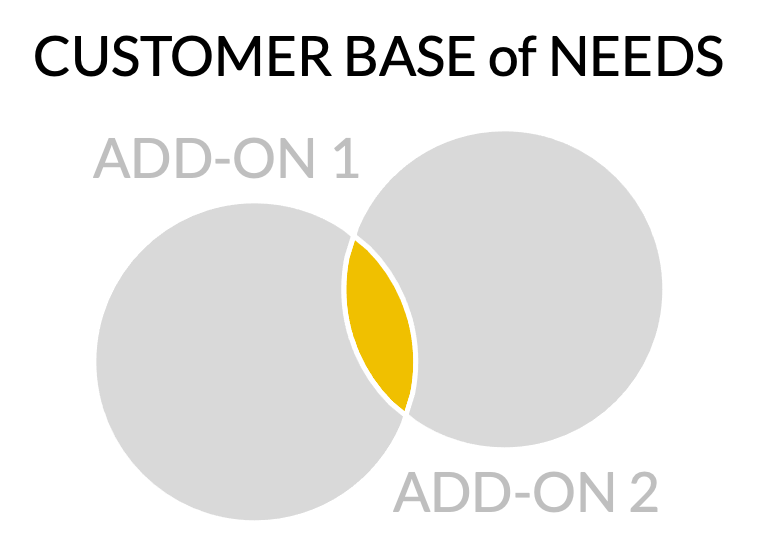

But the more you bundle together, the more this 1:1 correspondence gets jeopardised.

The intersection of two different features is always smaller as there is rarely a perfect match.

The same goes for the journey of how the customer gets the products.

Though there can be a good story why the Premium Winter Package is great for those who use their cars a lot during the winters, winter tires apply for all of them, while heated seats are more for those who park outside. The sub-segments can differ in the exact needs.

One of the main issues with add-ons is that they are cheaper so their incentivisation is limited for the front line. Packaging and bundling can solve this as the value increases.

What is alarming in this table is that you can solve one issue with a tool, but that doesn’t fix the other issue. Even worse, the potential fixing tools can play against each other in certain cases. That’s why managing add-ons is harder than changing the tires.

Not every add-on fits neatly into the playbook we’ve outlined. Sometimes the very conditions that seem like disadvantages can flip into advantages — if you know how to play them. That’s why you can’t just copy-paste a strategy; you have to investigate the situation thoroughly, like a mechanic diagnosing a mysterious dashboard light.

Why do customers upgrade? For some, it’s the device itself (User A buys the “Business” edition because of the engine). For others, it’s the quality experience (User B buys the same “Business” edition because of the leather smell, the quiet cabin, the premium sound system). Either way, packaging quality elements can result in an upgrade.

Instead of the previous zero-sum game of bundling, sometimes a win-win can be created: the customer enjoys real benefits, while the company gets the upsell.

Playbook for the quality game:

Choice is good, but too much choice is like a dashboard with 200 buttons — intimidating. If you have too many add-ons, simplify:

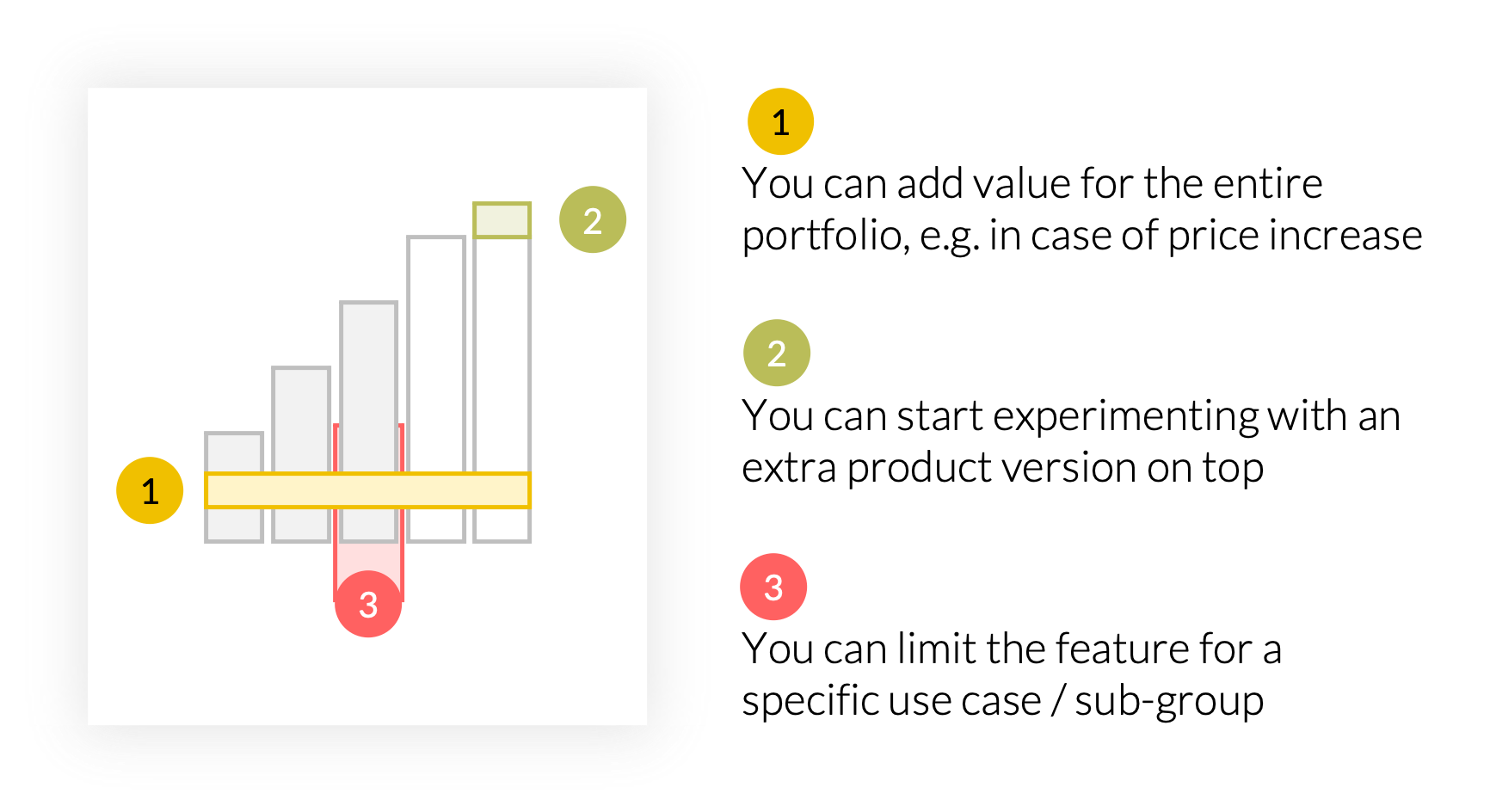

Most portfolios follow the small–medium–big logic. But you don’t have to wait until features become “expected” to build them into your core lineup.

Here’s how it works:

In other words: innovations and add-ons often debut in the luxury trim before trickling down to the mainstream. Just like adaptive cruise control started in high-end cars and is now standard on mid-range SUVs, the more-for-more strategy helps you balance experimentation with profitability.

Selling add-ons isn’t just about what you offer — it’s also about how you price and position them. Smart companies use a rhythm:

In subscription-driven businesses, the logic flips in interesting ways. You might start with a recurring subscription (the base service), then offer non-recurring add-ons (e.g. a one-time premium feature). Once customers see the value, you can shift those into recurring offers — creating a rhythm where the upsell and cross-sell cycle keeps the revenue engine humming.

To earn a place for the add-ons next to the inertia of the core portfolio, somehow you need to get over the burdens of smaller business impact, less channel capability and less incentive possibility.

So, how do you make add-ons more than an afterthought? Here are some solid lessons.

If you don’t have a responsible person or group that is interested in elevating the performance of the add-ons, the business as usual will eat up all the room for sure. Some businesses spin off separate entities to handle add-ons so the core team doesn’t get distracted.

Customers don’t instantly buy into new models like “heated seats on subscription.” It takes years of education (and maybe a bit of arm-twisting) for these add-ons to become normalised. Remember when paying for GPS felt weird? Now it’s standard.

BMW didn’t just slap a turbo on their sedan and call it a day. They created M Division, a dedicated performance unit. Similarly, companies sometimes need a whole team, channel, or even sub-brand to make add-ons fly.

You can also separate the different products in time. Dealerships sell the cars, but aftermarket shops thrive on accessories.

The car industry knows the secret: people don’t buy a car; they buy mobility, status, comfort, and a bit of bragging rights. The core product gets them from A to B, but the add-ons make them feel like it’s their car.

For other companies, it’s the same. The core portfolio is the stable, reliable revenue engine. But add-ons:

The challenge is execution. The trick is to treat add-ons not as a side hustle but as a strategic engine in their own right. Success doesn’t come from just having a car for every segment. It comes from making each of those cars feel like theirs.